Most of us work hard to improve our material circumstances, assuming that this is the key to happiness. According to research in psychology and economics over the past few decades, however, this assumption is mistaken.

While better circumstances can increase happiness to some degree — especially for people who have been facing particularly adverse conditions — for most of us, this boost is much less than we expect. It turns out that certain features of our minds work against our effort to reach happiness through material improvement, and that instead of just focusing on “getting more,” our pursuit of happiness would be more effective if we also focused on the kinds of activities that help us get the most out of what we already have.

In this module, we’ll combine expertise in psychology and philosophy to examine this empirical research on happiness and consider what implications it might have in our lives and communities.

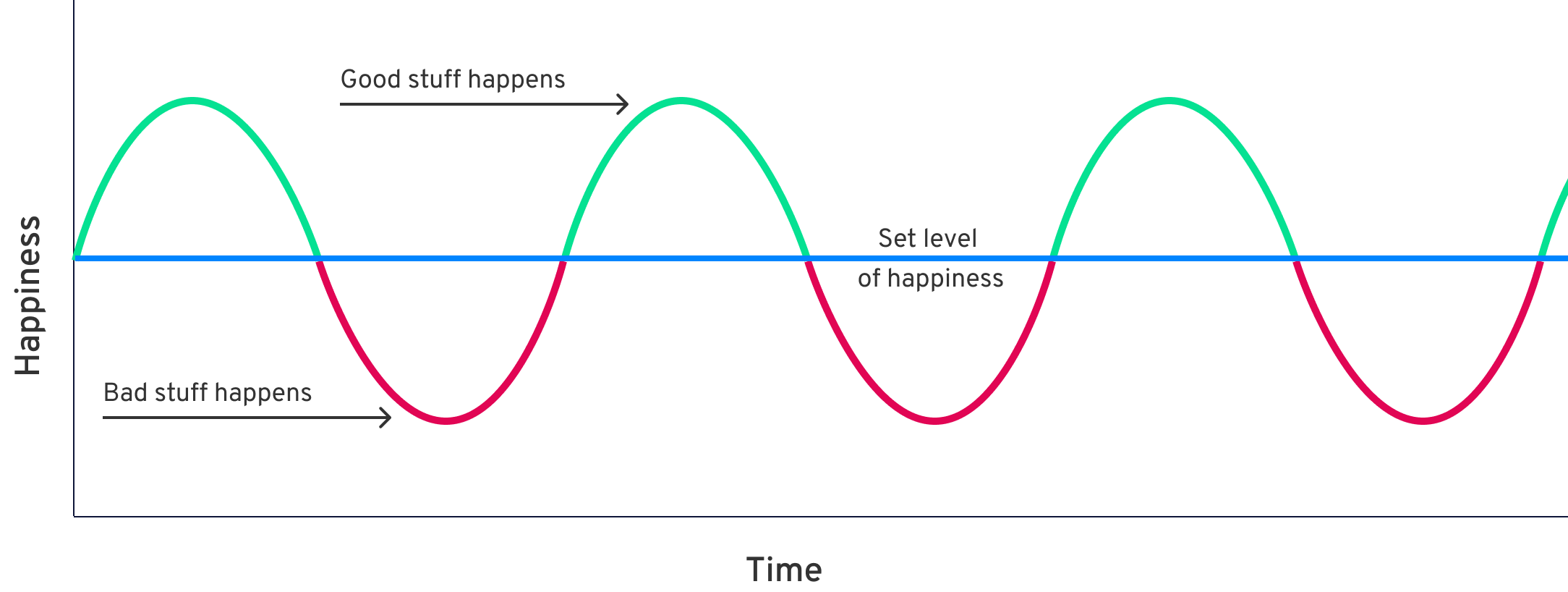

The module will begin with a set of videos by Dr. Laurie Santos, Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Science at Yale University, who will introduce key conclusions from the social science research to provide an empirically grounded understanding of how happiness works and what we can do to live happier lives. Critical questions will be raised as we discuss how scientists define and measure happiness; how psychological mechanisms like hedonic adaptation, shifting reference points, and immune neglect undermine our ability to translate material progress into real happiness; and how practices like mindfulness meditation, kindness, and gratitude can help us counteract these mechanisms and get us closer to the happiness we seek.

We’ll then turn to a series of philosophers to deepen our discussion. The philosophical lens will allow us to explore some important conceptual and ethical questions that arise as we try to interpret the empirical research and draw on its results for our own lives. We’ll see some different ways philosophers define happiness, using these conceptions to assess how empirical researchers define the phenomenon. We’ll also investigate challenging ethical issues, such as the extent to which a person’s happiness is their own responsibility, the ethics of being happy in a world full of suffering and injustice, and the lessons we should take from empirical happiness research in shaping our laws, policies, and social norms.

By the end of this module, learners will be familiar with several central conclusions drawn by empirical researchers who study happiness; they’ll see how critical thinking reveals key philosophical complications faced in the interpretation and application of these conclusions; and ultimately, they’ll be better positioned to articulate and pursue a vision of happiness that fits their own lives.