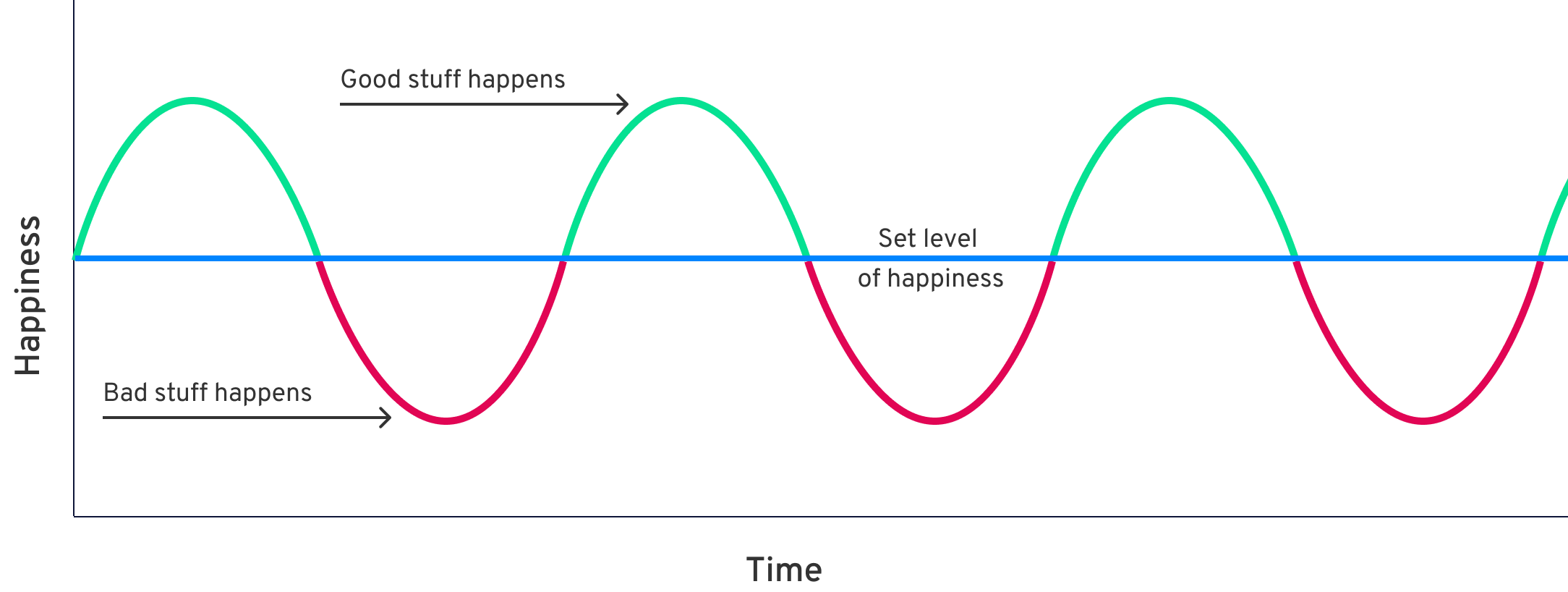

All of us aim to find happiness, but our attempts to achieve it frequently fail. Working hard to improve our circumstances often leaves us less happy than we started out. Why is this? And how can we do better? In this module, we’ll follow an inquisitive character named Maya as she explores the science and philosophy of happiness with the help of two Yale scholars.

Drawing on the growing body of empirical research on the topic, Dr. Laurie Santos (Professor of Psychology and Head of Silliman College) guides learners through key conclusions from the science of happiness to provide an empirically grounded understanding of how happiness works and what we can do to live happier lives.

Coming at the topic from a philosophical angle is Dr. Tamar Gendler (Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Vincent J. Scully Professor of Philosophy, and Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Science), who introduces us to different ways philosophers define happiness, and helps us use these conceptions to think about how to apply the results of empirical research to our own lives.

In the first lesson, Dr. Santos begins our journey by introducing Maya to research showing that improvements in material conditions have limited effects on happiness. In the second, she helps her understand how researchers define and measure happiness. These definitions lead to some philosophical questions about what happiness is.

We enter the philosophical side of this investigation in the third lesson, as Dr. Gendler presents the perspective of philosophical hedonism, which holds that happiness is primarily a matter of feeling good and enjoying life. In the fourth, Dr. Gendler guides Maya through a different conception of happiness, which holds that happiness is all about fulfilling your deepest desires.

Next, Dr. Santos introduces Maya to research showing that most of us are pretty bad at predicting how changes in our lives will impact our happiness, and describes some of the psychology underneath this limitation. In the sixth lesson, she helps us understand the cognitive biases that explain why improvements in income and circumstances usually fail to improve our happiness as much as we think they will.

In the remaining lessons of the module, Maya learns about another, and seemingly more effective, approach to the pursuit of happiness, drawing on both ancient philosophical insights and cutting-edge research.

Establishing a core assumption behind this alternative approach, the seventh lesson introduces the dual systems model of the mind, comparing it with earlier theories from Freud and Plato. These similar views all suggest that conflict among the different parts of our minds is a major impediment to happiness, bringing us to the eighth lesson, in which Maya explores the ancient idea that a certain kind of inner harmony — where each of our parts is functioning as it should — is the key to happiness.

Getting our parts in line, however, is easier said than done. It requires changing our habits. Thus, in the ninth lesson, Dr. Santos discusses several habits, or practices, that have been shown by researchers to reliably improve happiness. And in the tenth and final lesson, Dr. Gendler helps Maya see the deep importance of friendship in the effort to change her habits and put herself on the path to genuine and lasting happiness.